Have you ever wondered how seemingly ordinary individuals can come together to create extraordinary social movements? What makes people, who may have drastically different backgrounds and opinions, unite and act in unison to spark change? This is where the concept of collective action, a key focus within sociology, comes into play. One foundational theory that assists us in understanding this phenomenon is the **value-added theory**.

Image: www.slideserve.com

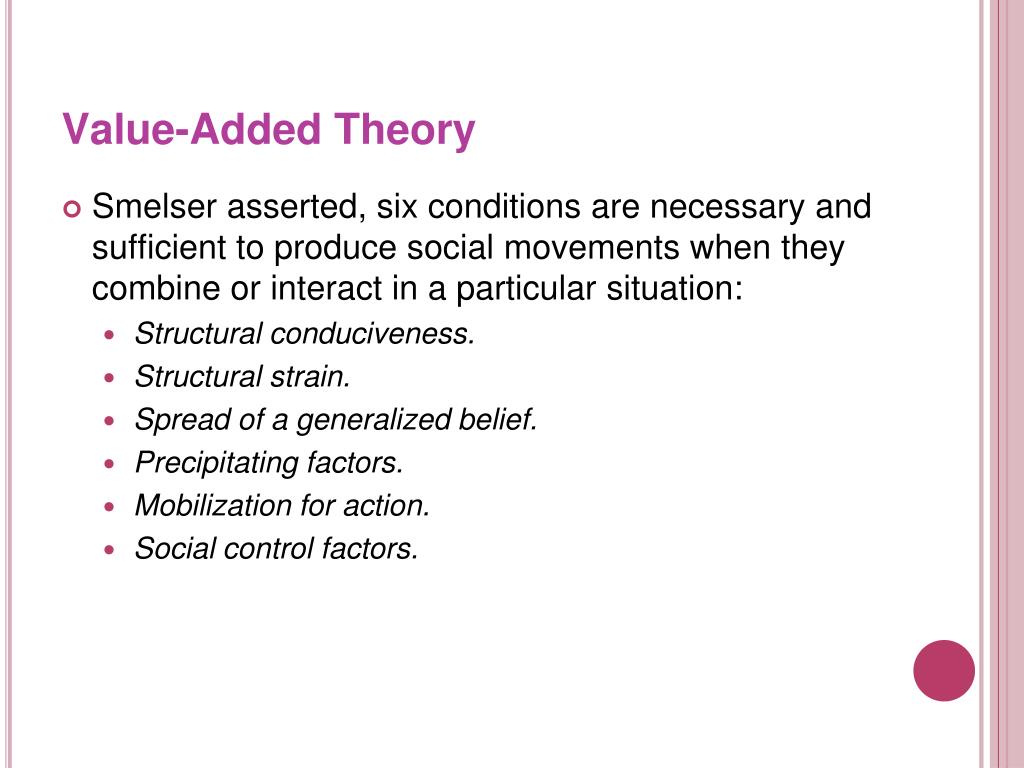

This theory, developed by sociologist Neil Smelser, serves as a framework for analyzing how social movements arise and evolve. It postulates that collective action, while seemingly spontaneous, is a result of a series of specific events and conditions that add value to the movement and propel it forward. In essence, the value-added theory helps us break down the complex process of collective action into manageable steps, offering a comprehensive lens through which to understand its dynamics.

Understanding the Core Concepts

The value-added theory is rooted in a set of six fundamental conditions, each contributing significantly to the emergence and growth of a collective action. Think of these conditions as building blocks, each adding a crucial layer to the foundation of the social movement.

1. Structural Conduciveness

This condition refers to the presence of existing social structures or conditions that make collective action possible. It’s the fertile ground on which the seeds of a movement can take root. For example, the presence of a strong social network or a shared sense of grievance can act as a catalyst for collective action. Imagine a community facing a common challenge like environmental pollution. The shared grievance against this issue can lead to a sense of solidarity and a collective desire for change.

2. Structural Strain

This condition represents the breakdown of existing social norms and structures, creating a sense of strain and dissatisfaction. Think of it as a crack in the pavement, a weakness in the system that allows discontent to bubble to the surface. The social strain might be triggered by economic inequality, political corruption, or social injustices. It’s this discontentment, this sense of wrongness, that leads people to question the status quo and seek a change.

Image: www.ucpress.edu

3. Generalized Belief

Here, a shared interpretation of the social problem arises, leading to a sense of collective understanding and agreement. It’s the moment when the “aha” moment occurs, when people realize they’re not the only ones experiencing the strain and that there’s a common problem demanding a collective solution. The emergence of a symbolic figure, a charismatic leader, or a specific event can help solidify this shared belief, acting as a rallying point for the movement.

4. Precipitating Factors

These are the events or incidents that trigger the immediate mobilization and action. It’s the spark that ignites the flame. This could be a specific incident of discrimination, the passing of unjust legislation, or even the success of a similar movement elsewhere. The precipitating factor turns the generalized belief into a tangible call to action, transforming simmering discontent into an unstoppable force.

5. Mobilization for Action

This condition signifies the process of organizing, recruiting, and actively engaging individuals to participate in the movement. It’s the development of strategies, the establishment of communication networks, and the recruitment of leaders who can coordinate the movement’s activities. A key aspect of this condition is the establishment of a shared goal, a clear objective that unites the movement’s participants and gives direction to their efforts.

6. Social Control

This refers to the measures taken by authorities to either suppress or manage the movement. It’s the counter-force to the collective action, the response of those in power to the perceived threat of the movement. There are various forms of social control, ranging from passive inaction to forceful repression. The response of authorities can play a crucial role in shaping the future direction of the movement, potentially either fueling its momentum or causing its decline.

Examples in Action

The value-added theory is not just a theoretical framework. It can be applied to understand the complex dynamics of numerous real-world movements. Let’s take a look at some examples:

- The Civil Rights Movement: This movement arose in response to structural strain rooted in deeply ingrained racial segregation and discrimination. It was fueled by the shared belief in equality and justice, ignited by the precipitating factor of Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a bus. The mobilization of action involved individuals and organizations like the NAACP, SCLC, and SNCC. The social control imposed by the authorities included the use of violence, segregationist laws, and media manipulation. However, the movement persisted, ultimately contributing to significant legal and social change.

- The Arab Spring: This popular uprising was driven by structural strain related to political corruption, economic inequality, and social oppression. The generalized belief in the need for democratic change was ignited by the self-immolation of a Tunisian street vendor, a precipitating factor that set off a chain reaction of protests across the Arab world. The mobilization of action was facilitated by social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, creating communication networks and rallying individuals to participate in the movement. The social control implemented varied across nations, ranging from suppression tactics to more moderate attempts at reform.

Value-Added Theory: A Critical Perspective

While the value-added theory offers valuable insights into the dynamics of collective action, it is not without its limitations. Some criticisms of the theory include:

- Linearity: The theory is criticized for its linear approach to collective action, suggesting a step-by-step progression that may not always reflect the complex and dynamic nature of social movements.

- Oversimplification: The theory is accused of oversimplifying the complex processes involved in the emergence of social movements by ignoring the intricacies of individual motivations, cultural influences, and power structures.

- Deterministic: The theory is perceived as deterministic, suggesting that collective action is an inevitable outcome of certain conditions. This ignores the role of agency and the ability of people to choose and shape their actions, even in the face of social pressures.

The Ongoing Relevance of the Value-Added Theory

Despite its limitations, the value-added theory continues to offer a valuable framework for understanding the development of collective action. It provides a helpful lens through which we can analyze historical and contemporary social movements, recognizing the factors that contribute to their emergence, growth, and outcomes. Moreover, it encourages us to consider the interconnectedness of social structures, individual beliefs, and collective actions, highlighting the complex and dynamic nature of social change.

Applying the value-added theory to contemporary social movements like the Black Lives Matter movement, the #MeToo movement, and the climate change movement can offer rich insights into the motivations, strategies, and challenges faced by these movements. Moreover, it can help us understand the role of social media, technology, and global interconnectedness in shaping the dynamics of contemporary collective action.

Value-Added Theory Sociology

Conclusion

The value-added theory, while not without limitations, provides a valuable foundation for understanding the rise and development of collective action. It helps us analyze the intricate interplay of social conditions, individual beliefs, and collective mobilization, offering a lens through which to examine the complex and dynamic nature of social movements. By recognizing the crucial elements that contribute to the emergence of collective action, we can gain a deeper understanding of social change, its causes, and its potential impact on society. Further exploring the latest advancements in social movement research and analyzing contemporary cases of collective action can deepen our understanding of these crucial social phenomena, empowering us to engage meaningfully in the ongoing process of social transformation.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/OrangeGloEverydayHardwoodFloorCleaner22oz-5a95a4dd04d1cf0037cbd59c.jpeg?w=740&resize=740,414&ssl=1)